Return to Teacher Resource Guide Home

‹ Pre-Show Activities | Post-Show Activities ›

Character Profiles

Listed in Order of Appearance

Revolutionary War Soldiers | Marcus | George Washington | James K. Vardaman | Lenora Ann Connors

Elizabeth Cady Stanton | Lucretia Mott | Frederick Douglass | Peggy Baird Johns | Lucy Burns

Martin Luther King Jr. | Sojourner Truth

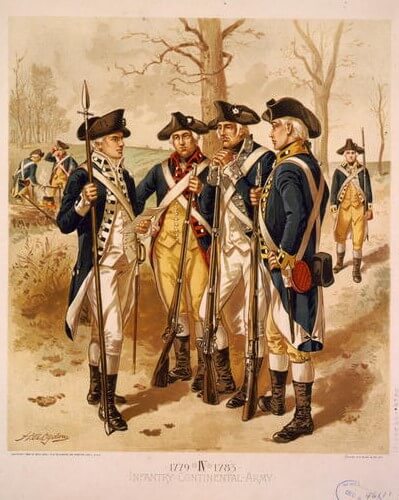

Revolutionary War Soldiers (Peterson, Stephens, Marcus):

The Experience of Valley Forge

The soldiers mentioned here are fictional, but the information reflects the experiences of real-life soldiers in the Continental Army stationed at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in the winter of 1777-1778.

The winter of 1777-1778 was a major turning point of the Revolutionary War. The British had taken over Philadelphia (then the capital of the United States) and the Continental Army (roughly 11,000 men with George Washington) was sorely lacking in supplies that Congress did not have the ability to send. Congress urged Washington to attack the British, but instead he led his troops to Valley Forge to recover. Valley Forge, located on the banks of the Schuylkill River, would be an easy location for the soldiers to defend themselves if the British were to stage an attack. There, soldiers faced starvation, illness, and bitter cold. Washington knew that he was in a perilous position both with his men and with Congress. Congress was on the verge of replacing him, and soldiers started to desert the army. Soldiers who attempted to desert were whipped or shot on sight. Those who remained loyal to Washington had his unfailing gratitude. All who stayed observed that he suffered with his men, refusing to abandon them even amidst such hardship. He dealt with Congress with his characteristic unflappable calm by telling them that if they could find a better commander, he would happily retire to Mount Vernon.

In the meantime, Washington enlisted some help to get his beleaguered army into shape. There were three primary boons that came to the army by February of 1778. The first was the Prussian General Friedrich von Steuben, who taught the rag-tag army how to be soldiers. The second was Nathanael Greene who took over the responsibility of finding supplies. The third was the agreement of France to join in with helping the Continental Army in February of 1778. Ultimately, Valley Forge solidified the intense loyalty of the army to George Washington’s leadership, and when the troops eventually left Valley Forge in June of 1778, they were ready to face to British. In fact, nine days after they left, they gained victory over the British at the Battle of Monmouth. Valley Forge became a symbol of the proving ground of what would become the army of the United States of America.

For more information, visit: http://history.com/this-day-in-history/washington-leads-troops-into-winter-quarters-at-valley-forge and https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/continental-army-enters-winter-camp-at-valley-forge

Photo: Infantry: Continental Army, 1779-1783, IV / H.A. Ogden ; lith. by G.H. Buek & Co., N.Y. – Library of Congress

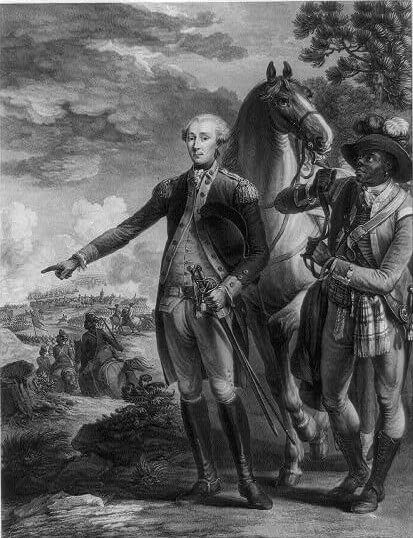

Marcus:

The Experience of Black Men in the Revolutionary War

Black men joined the army for different reasons than white men. Most believed that joining the army would earn them freedom after the war. As a result, there were black soldiers on both sides of the conflict, with men joining whichever side they felt most likely to free them from slavery after the war was over. The majority of these men served for the British (roughly 20,000) while between 5-8,000 served with the Patriots. Although Marcus is a fictional soldier, there are several named black soldiers who played important parts in the Revolution. For instance, Crispus Attucks was a runaway slave who took part in the incident that became known as the Boston Massacre. He is believed to be the first of the five colonists who were killed, making him the first American martyr. Another important soldier was Salem Poor, a man who bought his own freedom prior to the war. Historians believe he fought in several important battles, but he is most noteworthy for killing British Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Thanks to the musical Hamilton, the Marquis de Lafayette has gained renewed notoriety in our knowledge of the Revolutionary War, but Lafayette’s success would have been impossible without assistance from James Armistead. Armistead, a runaway slave, was charged with being a double agent because of his great knowledge of the local geography. He would pretend to be a runaway slave escaping to the British Army, where he would gather information and return it to the Marquis de Lafayette. The British Army even enlisted him to be a double agent for them because his knowledge was so respected. Unfortunately for the British, Armistead was a loyal Colonist, and everything he learned was reported back to his commander. Without Armistead’s information, the Continental Army would not have had the information they needed to win the Battle of Yorktown, which effectively ended the war. The Marquis was so grateful for Armistead’s efforts that he later helped to secure Armistead’s freedom, and James changed his last name from Armistead to Lafayette.

To learn more about other Black men and women who played significant roles in the Revolutionary War, visit history.com/news/black-heroes-american-revolution for some additional information.

Photo: Conclusion de la campagne de 1781 en Virginie. To his excellency General Washington … / peint par L. le Paon peintre de Bataille de S.A.S. Mgr. le Prince de Condé ; gravé par N. le Mire des Academies Imperiales et Royales et de celle des Siences [sic] et Arts de Rouen et de Lille. – Library of Congress

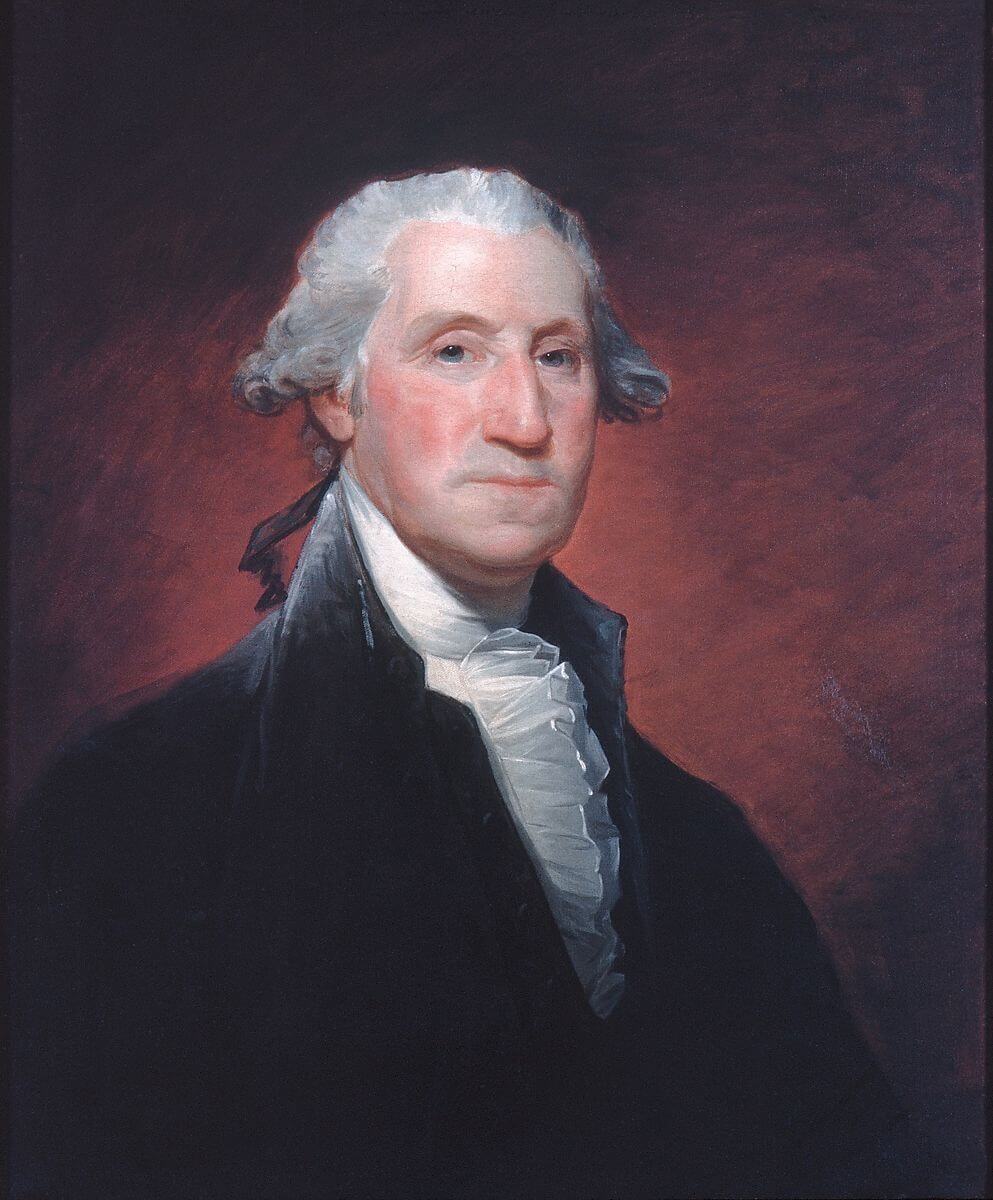

George Washington

February 22, 1732-December 14, 1799

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 in Virginia. His father owned a plantation on Popes Creek and served as a justice in the county’s court while he was young. George was the first son of his father Augustine’s second wife, Mary, after Augustine’s first wife died in 1729. When George was only two, his father moved his growing family to Little Hunting Creek Plantation (which later became Mount Vernon). Later, the family moved to another family property, Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia, where George spent most of his childhood. Most of what we know about Washington’s childhood is based more in speculation than fact (including the famous story about his chopping down the cherry tree). We do know that while the Washington family owned several properties, they were not considered wealthy by the standards of the day. We also know that George took on a good deal of responsibility in managing the house where his mother lived after his father died when he was only eleven, which taught him the need for responsibility from a very early age.

Although Washington’s older brothers were able to attend colleges in England, because of Augustine’s death, there was no money for Washington to attend an established school. Instead, Washington was educated at home. Still, he loved to learn and had a great passion for reading. One text that was especially important to him was called The Rules of Civility. He copied all 110 rules into his own notebook when he was a teenager. These rules included advice on how to behave in a way that brought honor to yourself and others. Washington took these guidelines to heart and was later known as a man of great courtesy and unflappable calm.

As an adult, Washington worked as a land surveyor, then later as a Major in the French and Indian War. These two experiences taught Washington a great deal about the land of the North American continent, as well as the skills needed to lead an army. After the war, Washington eventually joined the Virginia House of Burgesses, which led to his eventual appointment as head of the Continental Army. Washington’s famous military maneuvers include the crossing of the Delaware River and of course, the darkest time for Washington, Valley Forge. The brutal winter of 1777 did not break his spirit or his army’s; they emerged after six months still intact. In 1781, Cornwallis surrendered his forces at Yorktown to Washington, his counterparts, and French allies. This led to the close of the war.

Photo: George Washington by Charles Willson Peale ca.1779-81 – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

George Washington Continued…

∨

George Washington Continued

After America’s victory and finally winning their independence, Washington hoped he could resume a quiet life. In 1787, he was called again to serve his country, but this time to help unify disparate states, unrest, and a country still at odds. The Constitutional Convention led not to additional amendments, but rather a new Constitution with Washington unanimously voted as president. After two terms, he refused a third in order to retire to Mount Vernon. He died in 1799, leaving an undeniable legacy.

One final note on George Washington is in his role as slaveholder. He inherited ten slaves upon the death of his father, purchased some slaves, and inherited many more when he married his wife Martha. He owned approximately 40 slaves in 1759, but by 1799, he had more than 300. Washington accepted slavery as a young man and treated enslaved people like a slaveholder did, including whipping them, separating families, and re-capturing anyone who attempted to flee. He began to question the practice as he got older and had many contradictory views on slavery toward the end of his life. He rarely spoke out about the issue, fearing that it would break the fledgling country, but he did include that the slaves he was legally allowed to free should be freed upon his wife’s death. He was the only slaveholder among the founding fathers to make this stipulation, though in the end, only one of his slaves was set free.

For more information, visit www.mountvernon.org, https://www.history.com/news/did-george-washington-really-free-mount-vernons-slaves

Photo: George Washington by Gilbert Stuart – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

James K. Vardaman

July 26, 1861-June 25, 1930

J.K Vardaman was proud to have been born in the Confederate United States. He was known as “The Great White Chief” because of his intense support of white supremacy, once saying “If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy.” He was not shy about his prejudice, and worked throughout his political career in Mississippi to keep black citizens from voting, including supporting poll taxes, literacy tests, and barriers to registering for the vote. He targeted his rhetoric to the poor white population of Mississippi where he gained most of his support. He served as the Governor of Mississippi from 1904-1908 and then as Senator from Mississippi from 1913-1919, where he sought to repeal the 14th and 15th Amendments to the US Constitution (which had granted rights, including the right to vote, to black citizens.) To this day, Vardaman’s name graces an administrative building on the campus of the University of Mississippi, even though the university announced in 2017 that his name would be removed from the building.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_K._Vardaman and https://catalog.olemiss.edu/university/buildings

Photo: James K. Vardaman, half-length portrait, seated – Library of Congress

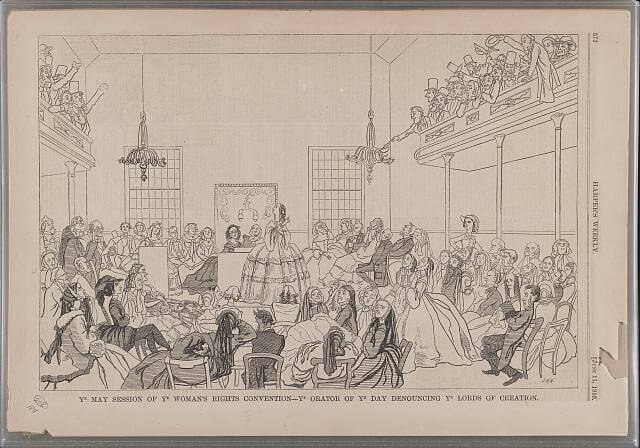

Lenora Ann Connors:

The Early Fight for Women’s Rights

Although Lenora Ann Connors is fictional, she represents many women who began the campaign for women’s rights in the early-mid 1800s. During this time period before the Civil War, all white men had the right to vote, no matter how much money or property they had. This same right was not extended to women. At the time, it was still assumed that women would naturally vote the same as her husband and that her vote would be redundant. These beliefs were part of what was eventually called the “Cult of True Womanhood,” which was the idea that the social belief woman would be pure, virtuous, pious, and submissive to her husband.

In the early 1800s, women started to voice their opinions on a number of issues, including temperance, slavery, religion, and suffrage. For at least twenty years, these ideas brewed in the minds of women, but especially in those of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who led the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

For more information about the evolution of the right for women to vote, visit www.history.com/topics/womens-history/the-fight-for-womens-suffrage

Photo: Ye May session of ye woman’s rights convention – ye orator of ye day denouncing ye lords of creation – Library of Congress

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

November 12, 1815-October 26, 1902

Elizabeth Cady Stanton received a unique education. The daughter of very wealthy parents, Elizabeth attended excellent schools. Some of her best education also came at home. Her father was a politician and lawyer, and Elizabeth paid keen attention to her father’s legal discussions from a young age. She was a bright, intelligent woman with many opinions of how the world could be improved. Her passion was shared by Henry Stanton, an abolitionist politician. Elizabeth and Henry married in 1840. They went to London on their honeymoon to attend a World Anti-Slavery convention, where Henry was slated to speak. While at the convention, Elizabeth met Lucretia Mott. The two of them bemoaned that women were excluded from participation at the convention (initially they were not allowed to attend, but they were eventually allowed to watch the proceedings from a separate location, though still forbidden to speak), and the two determined that they would host a women’s rights convention when they returned to America.

Their dream came true in 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention. There, Elizabeth presented “The Declaration of Sentiments,” a document that expanded on “The Declaration of Independence” by adding the word “woman” or “women” throughout the text. At the convention, women outlined several points of grievance, including the need for suffrage, for custody of children in the case of divorce, and a plea for the ability to hold property and control their own money. Elizabeth was passionate about many social justice concerns, but ultimately her focus settled on earning the vote for women, which would not happen until eighteen years after her death in 1902.

For more information, visit womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-cady-stanton

Photo: Elizabeth Cady Stanton – Library of Congress

Lucretia Mott

January 3, 1793-November 11, 1880

Lucretia Mott grew up in a Quaker family in Boston, Massachusetts. Quakers believed in the equality of all humans before God. From a young age, Mott believed that slavery and the subservience of women were morally incorrect. Mott later married an abolitionist who was very supportive of her work. Together, they worked to speak out against the dangers of slavery. Although there were many who believed that Mott speaking publicly against slavery was inappropriate because she was a woman, she was not deterred and continued her work because she knew it was the right thing to do. After meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the two of them worked together for a number of social causes, including women’s suffrage. Mott is quoted as stating that she grew up “so thoroughly imbued with women’s rights that it was the most important question” of her life. She is especially well known for delivering a lecture entitled “Discourse on Women” in which she outlined the history of the repression of women. Throughout her life, Mott worked to fight for the abolition of slavery and the right to vote for all citizens, no matter their gender or race.

For more information, visit: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/lucretia-mott

Photo: [Lucretia (Coffin) Mott, three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing right] – Library of Congress

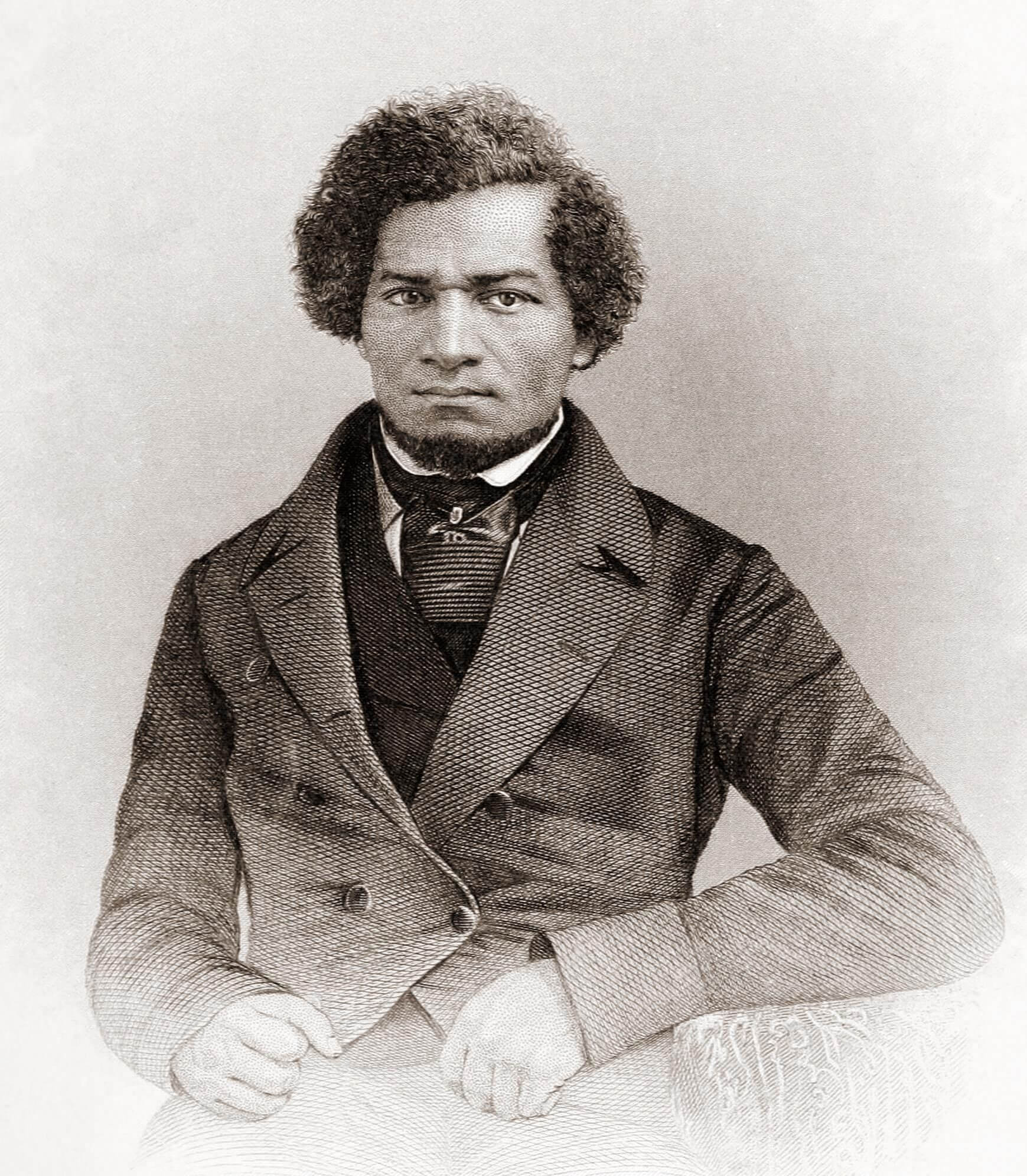

Frederick Douglass

Cir. February 1818-February 20, 1895

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery. At an early age he was taught to read by the mistress of the house, Sophia Auld. This ability to read and write was critical in Douglass’ life. He read everything he could and gained a firm belief in the immorality of slavery. After a few unsuccessful attempts, Douglass eventually escaped slavery for freedom and went to New York with a woman named Anna Murray, a free black woman who assisted him in his final attempt at escape. They eventually settled in Massachusetts. Douglass set to work spreading his ideas with a newspaper called The North Star, as well as other writing, including several memoirs about his time as a slave. He was also a regular speaker about the evils of slavery. He spoke in many places, but was not always met well. Mobs would often try to hurt him. In the 1840s, he had to escape to the United Kingdom for a while, just to avoid being recaptured and placed back into slavery.

In addition to being an abolitionist, Douglass was also an advocate for women’s rights and was a speaker at the Seneca Falls Convention where he stated that he did not believe it was enough to fight for black men to have the right to vote, but for all men and women to have the right to vote, regardless of the color of their skin, though he did support the 15th Amendment to the Constitution. Later in his life, he would be the first black man to have his name appear on the ballot of a presidential election (he was nominated, without his knowledge, to be Victoria Woodhull’s Vice President selection).

For more information, visit: https://www.biography.com/activist/frederick-douglass

Photo: Frontispiece: Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I- Life as a Slave, Part II- Life as a Freeman,with an introduction by James M’Cune Smith. – New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan (1855)

Peggy Baird Johns

Not much is known about Peggy Baird Johns’s early life. Most of our knowledge about her begins on September 25, 1917 when she was arrested in Washington, DC while protesting for women’s suffrage. She refused to pay her $25 fine and was sent to prison for a month. While in prison, she was kicked out of her apartment for failing to pay rent. That did not stop Peggy from working to help women earn the right to vote. After she was released from prison, she continued picketing and was arrested again in November of 1917 in what was called the “Night of Terror.” Peggy became known as one of the “militant” suffragists who were not afraid to face punishment as they fought for the vote.

For more information, visit: https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1009054704

Unable to find photos of Peggy, but photos of other women involved in the “Night of Terror” can be found here: https://www.history.com/news/night-terror-brutality-suffragists-19th-amendment

Photo: Women suffrage parade, Wash., D. C. – Library of Congress

Lucy Burns

July 28, 1879-December 22, 1966

Born in Brooklyn, Lucy Burns’ academic career led her to England where she got involved in the women’s suffrage movement in Scotland. She returned to the United States in 1912 where she helped found the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, which later became the National Woman’s Party. She edited The Suffragist which published material in supporting voting rights for women. She was active in many highly visible protests in Washington D.C. leading to her being arrested six times. She was an accomplished speaker who continued to rally people to the cause of women’s suffrage until 1920 when the 19th Amendment protected women’s right to vote in all states.

For more information visit https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lucy-Burns or https://suffragistmemorial.org/lucy-burns-1879-1966/

Photo: Lucy Burns, half portrait, seated. – Library of Congress

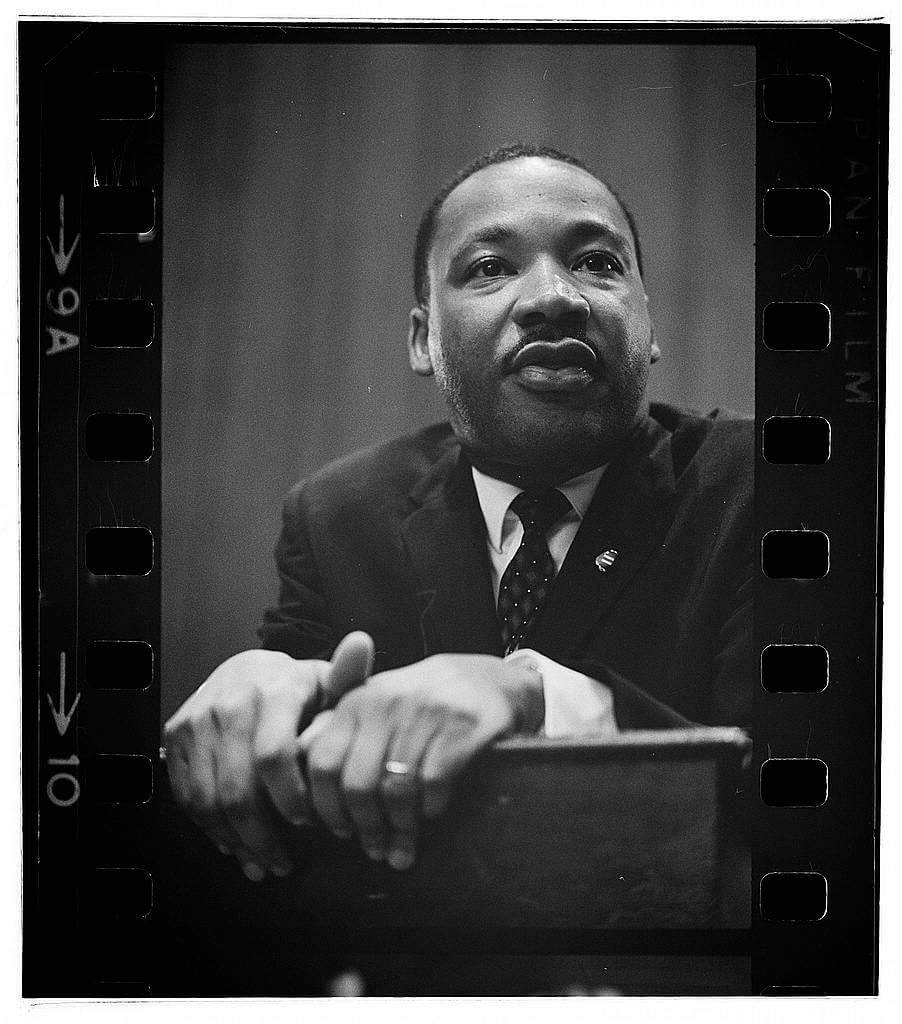

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

January 15, 1929-April 4, 1968

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. used his position as a Baptist reverend in Alabama to actively speak for equal rights during the era of widespread Jim Crow laws. He became a member of the executive committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Through his influence, he led southern blacks in many acts of resistance to the prevailing culture of prejudice. These acts of resistance, including bus boycotts, sit-ins, and voting marches, brought out violent reactions from government and law enforcement.

In response to the resistant violence against the Mississippi Summer Project designed to register blacks to vote, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led the famous march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama at which he spoke of his conviction to fight for voting rights for all

Blacks. Dr. King’s influence encouraged the passing of the 1965 Voting Rights Act which prohibited many of the tactics used to stop blacks from voting. He continued to push for resistance to prejudiced actions until his assassination in 1968.

For more information visit https://www.aclu.org/blog/voting-rights/promoting-access-ballot/remembering-dr-kings-defense-voting-rights or https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/biographical/

Photo: Trikosko, M. S., photographer. (1964) Martin Luther King press conference / MST. , 1964. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/

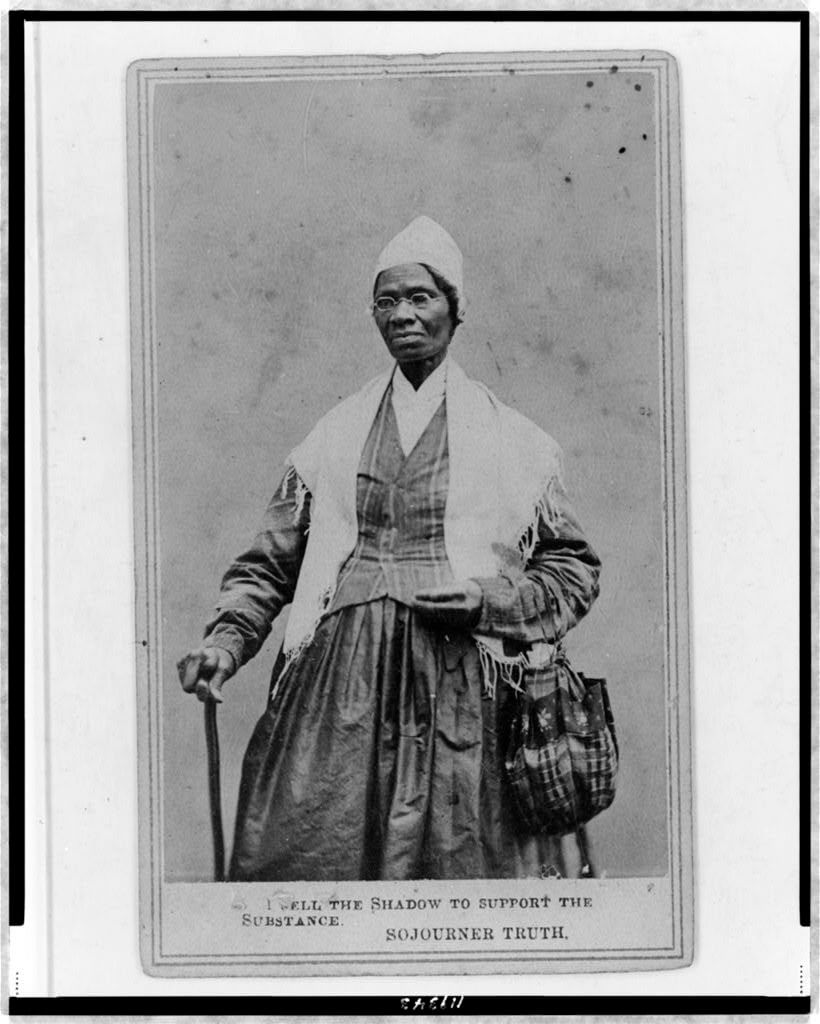

Sojourner Truth

1797-November 26, 1883

Sojourner Truth was born in 1797 as a slave in New York. She ran away from slavery and found shelter in the home of a local abolitionist family who bought her freedom. When her five-year-old son was illegally sold as a slave to a man in Alabama, she fought the sale in the court systems and eventually won. That victory represented one of the first examples of a Black woman successfully challenging a white man in court.

She spent the rest of her life fighting as an abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights. Without learning to read and write, she dictated her own story in The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave which sold widely. In 1851 at the Ohio’s Women’s Rights Convention, she gave a speech entitled “Ain’t I a Woman,” which was published and remains popular to this day. During the Civil War, she worked heavily for the cause of the Union, particularly using her influence to push for emancipation and to recruit Black soldiers for the Union army.

For more information visit https://www.biography.com/activist/sojourner-truth or https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sojourner-truth

Photo: [Sojourner Truth, three-quarter length portrait, standing, wearing spectacles, shawl, and peaked cap, right hand resting on cane] – Library of Congress